How Their Gardens Grow

Gardeners are inherently generous. Try to recall a summer that didn’t include a neighbor bringing over extra zucchini or a coworker piling a break-room table with tomatoes and okra, free for the taking. It’s not unusual to drive down the street and see a pile of plants with a hand-printed sign inviting folks to take whatever they like. So it’s no surprise, really, that community gardening has become such a movement in Nashville.

It doesn’t take much to start a community garden: just a plot of land and a desire to share. Some gardens are grown informally among a group of neighbors; others have sprouted up when a nonprofit wants to teach people in need how to grow their own food. Many gardens exist simply to offer opportunities people to connect with nature, in ways that otherwise wouldn’t be available. And while the folks who are involved in these group efforts seem to be very adept at the gardening, the common thread that runs through them all is the way the land and the plantings help bring communities closer together. Here are three examples of community gardens we love.

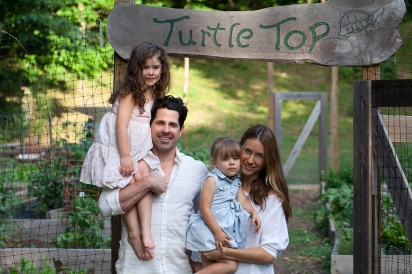

Turtle Top Neighborhood Garden

With their busy schedules and as parents of two young children, Kasey and JT Hodges ordinarily wouldn’t have time to garden, much less harvest the variety of fruits and veggies they’ll enjoy this summer. JT, a country artist on the rise, is on the road much of the time, promoting his new 6-song EP “Locks on Doors,” available on iTunes, and the trending single “Raybans,” playing on Sirius XM The Highway. Kasey works outside the home full-time, and when she is home, her 2- and 4-year-old daughters keep her occupied.

So when neighbors Kate Matthews and husband, artist Will Conner, started the garden and invited several families to participate, the Hodges found themselves in the thick of the gardening life, something that helps them feed their families more healthfully and also gives them something fun to do as a family. And even though there is the occasional squabble, like who should get the prize of the first ripe red strawberry of the year, that’s the sort of sibling rivalry a parent likes to

see.

The six families who share in the garden plots at Turtle Top also share in the responsibilities, emailing when someone spots a varmint nipping at the produce, collecting water in rain buckets and keeping the weeds at bay without the use of pesticides.

JT says it was the kids who made him realize they needed to get involved. He’d visited Turtle Top a few times, and when he saw how much his little ones enjoyed fruits and vegetables, he says, “Something clicked. I thought, we need to get the garden so the girls can know where all this comes from. I had to build my own raised beds. Once we got that part done, the whole family gets involved, whenever I’m home and not on the road.”

Neither JT nor Kasey were gardeners growing up, although JT remembers the excitement he felt growing up when his mother’s one summer garden experiment in Fort Worth produced a cantaloupe. Kasey says her mother was an avid flower gardener, but her parents never really had a vegetable garden at their Missouri home. Luckily, with a group project like Turtle Top, no experience is required because so many hands are involved.

“It’s great. When you go out of town, you have someone who will help water,” says Kasey. “It’s kind of like raising kids -- it takes a village.”

Donelson Community Gardens

Accountant Jan King didn’t really set out to create a nonprofit community garden that would serve as both an educational resource and a way to donate fresh produce to food banks. But then she started “connecting the dots” in her Donelson neighborhood. Initially she wanted her two teenagers to experience gardening (and the fresh produce it brings) like she had done as a child. But once she realized that schools in her community have high rates of children on free or reduced-price lunch and that she lived close to two senior living facilities, one a nursing home and the other assisted living, it clicked.

“I don’t know why, but it occurred to me that it would be beautiful if people of different generations could get together and grow food and teach each other and learn from each other,” says King, in her third year as director and founder of Donelson Community Gardens. “We don’t own it; we’re on Metro land near the Stones River Greenway. We’re in a good situation and a good location for everyone to come together.”

Each year, the garden gets a little more structure, she says. There are the beginnings of an orchard, with four peach trees. They have a blackberry patch and a blueberry patch. Rainwater is collected in barrels, no pesticides are allowed and they try to use as many heirloom varieties as possible with their tomatoes, cucumbers, corn, potatoes and beans. They also grow lots of herbs, including basil and “a huge amount of peppermint,” King says. Anyone is welcome to stroll the grounds, as long as they remember the things growing there belong to others and are not free for the taking.

It’s a popular spot for boaters, hikers, birders and photographers, King says. “Our main goal is educational and to provide healthy food… but we are also very much into the beauty of it. We plant extensive wildflower beds, and we have a rose-lined entry path.”

There’s also function behind the beautiful cosmos, marigolds, zinnias and wild bergamot, along with lemon balm, buckwheat, crimson clover, spearmint and asters. “We plant beneficial florals to take care of the bad insects, and we have a butterfly garden,” King says. “We grow milkweed for the monarchs because they’re kind of disappearing and are somewhat endangered right now.”

Volunteers help with demonstrations and maintaining the back half of the garden, where the nonprofit grows food that is donated to food banks, senior centers and needy families. People can lease 4x8 plots, and those who can’t afford it can apply for a box sponsored by someone or pay only a nominal fee. There are even 4x4 plots for children’s gardens, where they mostly grow herbs, tomatoes and strawberries.

King loves the diversity of the gardeners as well as the gardens. She enjoyed watching an 18-month-old, her youngest garden participant, bite into his first strawberry this spring. She also loves it when some of the nearby senior citizens, usually over the age of 70, make their way down the paths, sometimes with walkers, to watch the garden progress and talk to other gardeners.

Wedgewood Gardens and the Nashville Food Project

It’s a long way from Bhutan to Nashville. It’s even farther to Burma. And the distance between those cultures and our own may seem farthest of all. But those differences can melt away when a gardener can coax bitter gourd or even mustard greens from the Middle Tennessee soil.

“Our mission is to bring people together to grow, cook and share food,” says Christina Bentrup, garden manager for The Nashville Food Project, a 501(c)(3). “We do that in our gardens.”

Volunteers from all over Nashville -- including school and church groups, adults with developmental disabilities, homeless and jobless veterans and others -- help grow the fresh produce that helps feed the hungry. And while refugees from far-away lands may be working inthe gardens one day, on other days it’s just as likely to be children from the neighborhood.

Harvest Hands, a South Nashville nonprofit that helps teach leadership skills to elementary and middle school students through after-school and summer programs, brings groups of children to work in the gardens once or twice a week throughout spring, summer and fall, Bentrup says.

“We’ve worked with them for many years, and we love having them be a part of the garden,” she says, adding that the children learn to do everything from growing and harvesting to weeding and working with compost. The Nashville Food Project also provides twice-monthly meals for the parents and youths involved.

“We want to partner deeply in the Wedgewood-Houston neighborhood where our garden is located,” Bentrup says. “These are the people who live there, and we want to involve them in the garden. For us, it’s about engaging multiple facets of the neighborhood… What we have to offer is a beautiful, safe space where they can learn something about the food system, where food comes from and how to grow it.”

As part of their outreach efforts, which include preparing hot meals and delivering them to local populations in need, The Nashville Food Project teamed up with other nonprofits in town, the Center for Immigrants and Refugees in Tennessee (CRIT), Nashville Grown and the Tennessee Foreign Language Institute, to create the Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program. Three community gardens in Wedgewood and South Nashville give refugees from Bhutan and Burma a

place to grow, and to learn.

“They grow what you would find in a typical Southern garden -- tomatoes, peppers, greens, cilantro, other herbs -- and they also grow some of their crops from home, like mustard greens. Which is actually a very Southern thing, too,” says Bentrup of the Bhutanese immigrants, one of the largest refugee resettlement populations in Nashville. “They also grow some bitter gourd, which is very much like a cucumber but they cook it in milk. It’s considered a good food for the

heart, like medicine.”

The organic plots are cared for largely by former large-scale growers from Bhutan and Burma,and the Nashville Food Project supports them through weekly trainings. The learning curve, she says, is “mostly about spacing.”

Lauren Bailey, who is director of Agricultural Programs for CRIT and manages the refugee gardening project, hopes the program will be able to expand in the future to include refugees from other countries. The new-to-Nashville residents work with interpreters to expand their skill sets, learn how to garden on a small scale and master new techniques. And, in addition to the benefits they get from being able to grow fresh vegetables common to both Middle Tennessee and their respective home countries, Bailey says, there are other, perhaps less obvious but equally important rewards.

“There's the more nuanced benefits that come with communal space, which might simply behaving another place to go to feel at home, or a place to reconnect with friends or a place to find solitude,” Bailey says.

“Some participants were farmers in their home countries, and some grew up around parents or grandparents who were farmers,” she says. “It seems that all of our participants share a love for food and enjoy the opportunity to provide for themselves and their families.”

To learn more about the community gardens featured in this article and how you can get involved, go to:

http://www.donelsoncommunitygardens.org/

http://www.thenashvillefoodproject.org/

http://www.centerforrefugees.org/